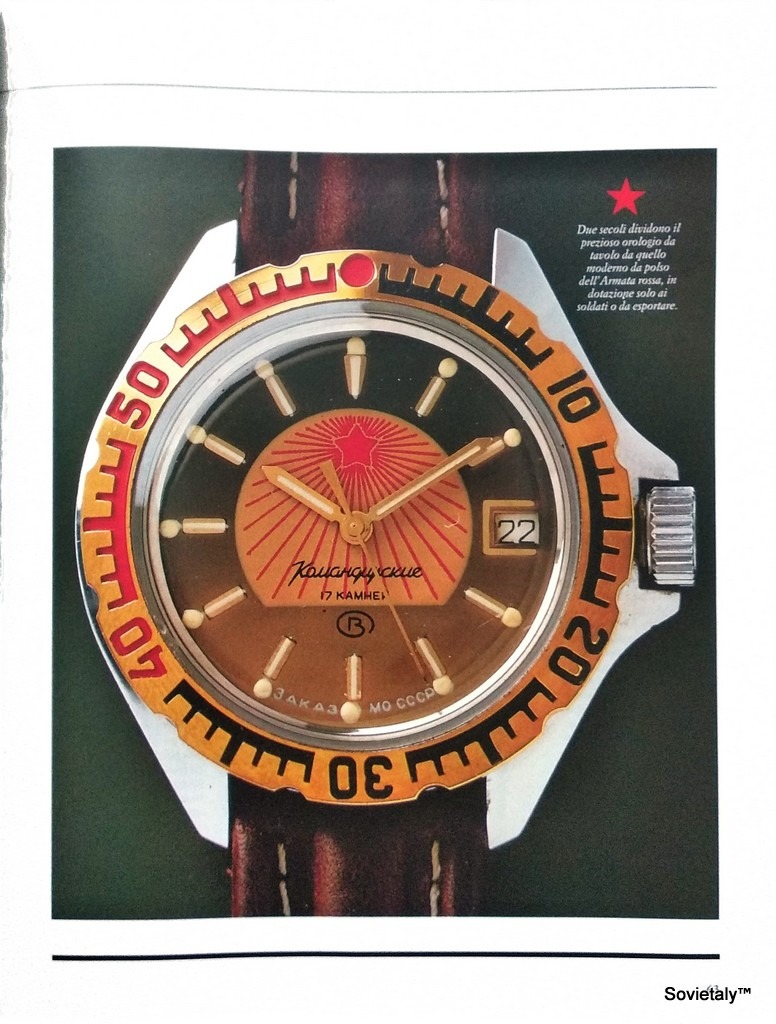

Introduction. On the late afternoon of Christmas Day 1991, millions of Soviet citizens watched in astonishment as a historic announcement was made: Mikhail Gorbachev, speaking live on television, declared he was ending his tenure as President of the USSR and thereby effectively pronouncing the end of the superpower born in 1922. This event marked the culmination of a dissolution process that had begun at least two years earlier, a watershed moment that radically transformed the world’s geopolitical balance. From the vast Soviet empire, 15 independent states emerged; even specific sectors like the Soviet watch industry experienced a sudden shock: the great watch factories (Poljot, Raketa, Vostok, etc.), long accustomed to central planning, suddenly found themselves without state support, forced to navigate the market economy on their own.

🚀 The Last Soviet Citizen

In December 1991 cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev was aboard the space station Mir. Launched into space as a Soviet citizen, he returned to Earth in March 1992 as a Russian citizen: during his mission the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. This anecdote vividly illustrates the epochal magnitude of that historical change.

In this article, we recount—without political judgments—the key events from 1989 to 1991 that led to the USSR’s collapse, then explore the birth of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and its subsequent failure. We will use authoritative historical sources and official documents (including the full text of Gorbachev’s famous speech in the original Russian and an English translation) to ensure accuracy and depth.

The Premises (1989–1990): From Eastern Europe to Internal Secessionist Pressures

The “end” of the Soviet Union did not happen overnight, but was the culmination of reforms and tensions that had been building for years. In 1985 Gorbachev launched the policies of perestroika (economic restructuring) and glasnost (political openness) in an attempt to renew the Soviet system. These reforms, while relaxing repression and easing the Cold War, also exposed the severe economic problems and national tensions that had long been suppressed.

- 1989: The year of revolutions in Eastern Europe. The USSR’s satellite states in Eastern Europe abandoned their communist regimes one after another. The iconic event was the fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989), which signaled the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet bloc in Europe. Gorbachev chose to not intervene militarily in the Warsaw Pact countries in revolt, breaking with the interventionist doctrine of the past. This decision earned the USSR international respect but also encouraged independence aspirations within the Union. By the end of ’89, the climate in the USSR had changed: on one side, reformers pushing for more change; on the other, conservatives alarmed by the disintegration of the system.

- 1990: The Soviet republics move toward autonomy. Within the USSR, the republics began proclaiming their own sovereignty. On March 11, 1990, Lithuania unilaterally declared independence – the first Soviet republic to do so (followed in the subsequent months by Estonia and Latvia). Moscow initially deemed these declarations illegal, but the signal was clear. In the months that followed, other republics also pushed for greater autonomy: for example, on June 12, 1990, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russia) adopted a Declaration of State Sovereignty, asserting the primacy of its laws over those of the Union; a few weeks later Ukraine did the same. In practice, while Gorbachev tried to negotiate a new federative pact to hold the USSR together, many parts of the federation were already paving the way for independence.

These centrifugal forces were accompanied by the sunset of the Soviet imperial order on the international stage. In 1990 the USSR consented to the reunification of Germany and severed the remaining ties of the old bloc: in 1991 both the Comecon (the communist economic alliance) and the Warsaw Pact were formally dissolved. Meanwhile, within the USSR, elements of democracy were introduced: in March 1990, relatively free elections were held in the republics, and the Communist Party lost its monopoly in several areas. Gorbachev himself, in March 1990, assumed the newly created position of President of the USSR (a role established for him) in an attempt to give the state a more presidential and less party-driven structure. Despite the international prestige he gained (Nobel Peace Prize in 1990), Gorbachev faced growing internal difficulties: a grave economic crisis, with shortages of consumer goods and inflation, undermined public confidence, while the republics pressed to break away and party hardliners accused him of having weakened the Union.

1991: Coup d’État and the Dissolution of the Soviet Union

The year 1991 was decisive. Events unfolded rapidly, from the dramatic August coup to the final collapse in December. Let’s review them in chronological order:

- March 1991: Referendum on the Union. In an effort to find legitimacy for a “renewed Soviet Union,” Gorbachev called a nationwide referendum on March 17, 1991. Citizens were asked whether they wanted to maintain the USSR as a federation of sovereign republics. Nine republics participated (the six most secession-minded – the three Baltic states, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova – boycotted the vote). The outcome apparently favored unity: about 76% of voters supported a reformed Soviet Union. This result showed that, despite everything, a large part of the population (especially in Russia, Belarus, Central Asia) feared disintegration. However, the apparent popular support for the Union was not enough to stop the course of events.

- June 1991: Yeltsin becomes President of Russia. Another sign of change came with the first popular presidential election in the Russian republic. On June 12, 1991, Boris Yeltsin – a reformist politician and outspoken critic of Gorbachev – was elected President of the RSFSR (Russian Federation) with 57% of the vote, defeating Gorbachev’s preferred candidate (Nikolai Ryzhkov). For the first time, Russia – the key republic of the USSR – had a president elected by popular vote, separate from and a rival to the Union’s president. Yeltsin became the champion of Russian sovereignty and of further market-oriented economic reforms. The Gorbachev–Yeltsin dualism grew increasingly tense: Gorbachev sought to save the Union via a new Union Treaty, scheduled for August 1991, which would have transformed the USSR into a looser federation; Yeltsin aimed to transfer powers from Moscow to the individual republics, defending the interests of the newly sovereign Russia.

- August 1991: Hardliners’ coup (“August Putsch”). On the eve of the new Union Treaty’s signing (set for August 20, 1991), the unexpected happened: on August 19, 1991, a group of high-ranking conservative Soviet officials attempted a coup in Moscow to halt the breakup of the USSR. Vice President Gennady Yanayev, Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov, Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov, KGB chief Vladimir Kryuchkov, and others formed a State Committee for the State of Emergency, declaring that Gorbachev (vacationing in Crimea at the time) was “incapacitated”. Tanks rolled through the streets of Moscow and a state of emergency was announced. The plotters belonged to the hardline wing of the regime, fearful that the new treaty would decentralize too much power and cause the Union to implode. The popular resistance and Yeltsin’s stance, however, doomed the coup: thousands of citizens flooded the streets of Moscow, erecting barricades to protect the White House (the Russian parliament) where Yeltsin had set up headquarters. In a famous scene, Yeltsin climbed atop a tank to rally the crowd and denounce the coup as illegal. The army hesitated to fire on the protesters; after three days (by August 21) the putsch collapsed. The coup leaders were arrested and Gorbachev returned to power, but he was now gravely delegitimized. The failed coup effectively ended the CPSU’s political dominance (Communist Party of the Soviet Union): the party was suspended and later banned in Russia, and Gorbachev’s authority – even though he had been the plotters’ victim – was irreparably undermined. As Gorbachev himself acknowledged in his final speech, “the August putsch brought the crisis to a head” and what followed – the dissolution of the Soviet state – was its most destructive consequence.

- Autumn 1991: The republics declare independence. In the aftermath of the failed coup, real power swiftly shifted to the republic leaders. Yeltsin, in Russia, assumed control of central institutions (he even ordered the red flag to be lowered from the Russian parliament building and Soviet symbols to be removed). The Union republics, one after another, declared their independence: on August 24, 1991, Ukraine proclaimed independence (confirming it later in a popular referendum on December 1, in which over 90% of Ukrainian citizens voted to leave the USSR). By the end of August, Belarus, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan had also declared independence; in September, Armenia, Tajikistan and the three Baltic states followed suit (their separation was finally recognized by Moscow on September 6, 1991). In short, within weeks the Soviet Union ceased to exist as a political entity: Moscow no longer exercised authority over the republics, which were now acting as independent states. Gorbachev made one last desperate attempt to maintain at least a minimal confederation among the new states, but the die had been cast.

- December 8, 1991: The Belavezha Accords – the USSR ends, the CIS is born. The final blow came at the beginning of December. On December 8, 1991, at a dacha in the Belavezha Forest (in Belarus), the leaders of Russia (Boris Yeltsin), Ukraine (Leonid Kravchuk), and Belarus (Stanislav Shushkevich) met secretly. They signed the Belavezha Accords, which formally declared the Soviet Union dissolved and announced the creation of a new entity, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The joint statement read: “The USSR, as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality, has ceased to exist.” It was an effectively revolutionary act: three founding republics of the USSR (Russia, Ukraine, Belarus) were renouncing the 1922 Union Treaty and sealing the end of the Soviet state. Gorbachev had not even been invited to this decisive meeting, a sign that his role was by then marginal. A few days later, on December 12, the Russian Supreme Soviet ratified the agreement and recalled the Russian deputies from the Union’s Supreme Soviet, completing the Russian secession from the USSR (in effect, the act that made the Union’s continued existence impossible).

- December 21, 1991: Alma-Ata Protocol. The Belavezha Accords invited all former Soviet republics to join the new CIS. On December 21, 1991, in Alma-Ata (Almaty, Kazakhstan), another eight leaders – including those of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Moldova – joined the Commonwealth by signing the Alma-Ata Protocols. Thus, 11 of the 15 ex-republics became part of the CIS (the only ones excluded were the three Baltic states, which had chosen an entirely independent, pro-Western path, and Georgia, which was then embroiled in internal conflicts and joined later in 1993). In these protocols, beyond expanding the CIS, the signatories confirmed the end of the USSR and agreed on principles of cooperation among the newly independent states.

- December 25, 1991: Gorbachev resigns on live TV. At this point the facts on the ground were accomplished: only the final formal act remained. On the evening of December 25, 1991, at 7:00 p.m. Moscow time, Mikhail Gorbachev appeared on central television to announce his resignation as President of the USSR. In his solemn address, broadcast worldwide, Gorbachev declared: “In consideration of the situation that has developed with the formation of the CIS, I hereby cease my activities as President of the USSR.”. He lauded the successes of the reforms and democratization since 1985 but expressed regret at the dismemberment of the Soviet state, stating he could not endorse that choice imposed by events. It was a historic and emotional moment: after nearly 70 years, for the first time there was no Soviet President and no Union government. That same evening, at 6:35 p.m., the red flag of the Soviet Union was lowered from the Kremlin and in its place the tricolor flag of the Russian Federation was raised. The USSR, born from the 1917 Revolution, effectively no longer existed.

- December 26, 1991: Official dissolution of the USSR. The next day, December 26, the final legal act took place: the Soviet of the Republics, the upper chamber of the Soviet parliament, passed a resolution formally dissolving the Soviet Union and abolishing all its institutions. At the same time, it recognized the independence of all the former republics. The largest country in the world by area had peacefully fragmented into a constellation of independent states. Fortunately – as Gorbachev would later emphasize – this happened without a full-scale civil war, a very real danger given the nuclear arsenal and ethnic tensions involved. The Soviet armed forces were placed under joint CIS command (temporarily) and then gradually under the control of the individual new states. Within days, all the former Soviet republics had achieved independence and the international community rushed to recognize them diplomatically.

9 November 1989 – Fall of the Berlin Wall

The barrier dividing East and West Berlin is torn down. It becomes the symbol of the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and foreshadows the end of Soviet influence in the region.

11 March 1990 – Lithuania declares independence

Lithuania, followed shortly by Estonia and Latvia, proclaims the restoration of its independence from the USSR. It is the first Soviet republic to do so, openly defying Moscow.

17 March 1991 – Referendum to save the USSR

A referendum is held in 9 republics: 76.4% of voters approve the proposal to maintain a “Union of Sovereign States.” The Baltic republics, Georgia, Armenia, and Moldova boycott the vote.

12 June 1991 – Yeltsin elected President of Russia

Boris Yeltsin wins the first presidential elections of the Russian Republic with 57% of the vote, defeating Gorbachev’s favored candidate. Russia thus asserts its political autonomy within the USSR.

19–21 August 1991 – Failed coup in Moscow

A group of hardline communist officials attempts a putsch to stop Gorbachev’s reforms. The population and Yeltsin resist: after three days the coup fails. The Communist Party is banned in Russia.

8 December 1991 – Belavezha Accords

Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus sign an accord that declares the Soviet Union dissolved and establishes the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The other former republics are invited to join.

25 December 1991 – Gorbachev resigns

In a televised address to the nation, Mikhail Gorbachev announces his resignation as President of the USSR and the end of the Union. The red flag over the Kremlin is lowered and replaced by the Russian tricolor.

26 December 1991 – Legal end of the USSR

The USSR’s Supreme Soviet officially declares the Soviet Union dissolved. The 15 republics are now fully independent states, marking the formal conclusion of the USSR’s history.

21 December 1991 – Alma-Ata Protocol (chronologically earlier than 25/12)

(Occurs just before 25/12) Eight other ex-republics (including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Armenia) join the CIS by signing the Alma-Ata Protocols. The CIS thus initially has 11 members, excluding the Baltic states and Georgia.

1992–1993 – Birth of the CIS and early frictions

The CIS members approve a Charter (January 1993) but Ukraine and Turkmenistan refuse to ratify it, opting for an associate status. This weakens the Community’s cohesion from the start.

August 2009 – Georgia leaves the CIS

Following its conflict with Russia (the 2008 South Ossetia war), Georgia formally withdraws from the CIS. It is the first country to leave the organization, underscoring its fragility.

May 2018 – Ukraine exits the CIS

Years after limiting its participation, Ukraine (the second most populous ex-USSR republic) ends all involvement in the CIS. By now the Commonwealth, without Ukraine and Georgia, has lost much of its original significance.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS): birth and decline

Objectives and early period. The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) was born, as we have seen, immediately after the dissolution of the USSR, with the expectation of maintaining a cooperative bond among the former Soviet republics. Initially, 11 states joined (all the former republics except the three Baltic states and Georgia, which would enter in 1993). The CIS was conceived as an international organization to manage the orderly transition of the post-Soviet space: to coordinate economic policies, oversee the division of the Soviet military and nuclear arsenal, facilitate trade relations, and possibly develop common policies in certain areas. Its administrative headquarters was set in Minsk (Belarus), and Russian was adopted as the organization’s official working language. In those early months, one urgent priority was ensuring control over the Soviet nuclear arsenal: warheads stationed in Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan were swiftly brought under unified oversight (and later transferred to Russia in the following years). On the economic front, efforts were made to prevent a complete collapse of interdependence: a de facto free-trade area was maintained, and members committed to cooperate so as not to abruptly sever the industrial supply chains developed in the Soviet era.

From the start, however, significant internal divisions emerged. Ukraine, for example, sought to limit its participation: although it took part in founding the CIS, it never ratified the CIS Charter adopted in January 1993, in part because it did not accept Russia being recognized as the sole successor state of the USSR (for instance, maintaining the USSR’s seat at the UN). Similarly, Turkmenistan did not ratify the charter, opting for a more loose “associate member” status. This meant that from the outset some key republics viewed the CIS not as a binding supranational entity, but rather as a voluntary forum.

The limits and failure of the CIS. Despite initial hopes, the CIS never developed into a deep political or economic union. By the mid-1990s it was clear that the organization was struggling to achieve its main objectives. According to many observers, even the CIS’s limited goals proved difficult to realize: the Commonwealth showed itself incapable of stanching the centrifugal forces and the conflicts among the former allies. For example, within a few years of independence, local conflicts erupted (the war in Nagorno-Karabakh between Armenia and Azerbaijan; the civil war in Tajikistan; the secessionist conflict in Transnistria in Moldova; the separatist wars in Georgia) without the CIS being able to do much to resolve them. Moreover, no common foreign or defense policy ever materialized: each country pursued its own national interests. Russia formed separate military alliances (like the Collective Security Treaty Organization, from which some countries later withdrew) and bilateral agreements, but the CIS as such remained politically weak.

It should be noted that some aspects of the CIS were functional: more than a purely symbolic entity, the Commonwealth did serve as a platform for dialogue and technical cooperation. On the economic front, for example, the major tangible achievement was the creation of a free trade area among many of the member countries, formalized through agreements implemented by 2005. The CIS also facilitated cooperation in areas like transportation, telecommunications, immigration policy, and the fight against organized crime. Remarkably, even at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, athletes from the former Soviet republics competed together under the CIS flag, honoring commitments made by the USSR before its dissolution. These positive elements, however, could not reverse the broader trend toward fragmentation.

During the 2000s, the CIS further waned in relevance. Georgia withdrew entirely from the organization in 2009, following its conflict with Russia, viewing CIS membership as incompatible with its pro-NATO orientation. Ukraine, which had always been a member in only a nominal sense, decided in 2018 to formally end its participation in the Commonwealth amid the ongoing crisis with Russia. Today (2025), the CIS mainly includes Russia and a number of Eurasian states (such as Kazakhstan, Belarus, Uzbekistan, and others), and serves an almost purely consultative role. In practice, the CIS never succeeded in achieving the political integration or strategic cohesion that some had envisioned in 1991, remaining a rather weak organization. Many of the former republics charted their own paths: the three Baltic states joined the European Union and NATO; Georgia and Ukraine pursued closer ties with the West; other countries engaged in alternative structures led by Russia (such as the Eurasian Economic Union, established in 2015).

In conclusion, Gorbachev’s announcement of December 25, 1991 was the culmination of a peaceful yet turbulent process of dissolution. That speech – which we present in full below, in Russian with an English translation – remains a moving testament to the end of an era. Gorbachev spoke of achievements and mistakes, of hope for democracy and anguish over the country’s breakup, and he wished the peoples of the former Soviet Union a prosperous and free future. Although the Commonwealth of Independent States that arose from the USSR’s ashes never became the integrated successor that some hoped, the fact that the Soviet colossus imploded without immediately descending into widespread chaos is an outcome many attribute to the measured leadership of figures like Gorbachev.

Below, we present the complete transcript of Mikhail Gorbachev’s December 25, 1991 address, in the original Russian with an English translation, as an invaluable primary source document.

The Speech of Mikhail Gorbachev – December 25, 1991 (original text and translation)

(Source: «Российская газета», December 26, 1991; Wikisource archive. English translation by the author, based on the official AP translation.)[rbth.com]

Original text (Russian):

«Дорогие соотечественники! Сограждане!

В силу сложившейся ситуации с образованием Содружества Независимых Государств я прекращаю свою деятельность на посту Президента СССР. Принимаю это решение по принципиальным соображениям.

Я твердо выступал за самостоятельность, независимость народов, за суверенитет республик. Но одновременно и за сохранение союзного государства, целостности страны.

События пошли по другому пути. Возобладала линия на расчленение страны и разъединение государства, с чем я не могу согласиться. И после Алма-Атинской встречи и принятых там решений моя позиция на этот счет не изменилась.

Кроме того, убежден, что решения подобного масштаба должны были бы приниматься на основе народного волеизъявления.

Тем не менее я буду делать все, что в моих возможностях, чтобы соглашения, которые там подписаны, привели к реальному согласию в обществе, облегчили бы выход из кризиса и процесс реформ.

Выступая перед вами последний раз в качестве Президента СССР, считаю нужным высказать свою оценку пройденного с 1985 года пути. Тем более что на этот счет немало противоречивых, поверхностных и необъективных суждений.

Судьба так распорядилась, что, когда я оказался во главе государства, уже было ясно, что со страной неладно. Всего много: земли, нефти и газа, других природных богатств, да и умом и талантами Бог не обидел, а живем куда хуже, чем в развитых странах, все больше отстаем от них.

Причина была уже видна – общество задыхалось в тисках командно-бюрократической системы. Обреченное обслуживать идеологию и нести страшное бремя гонки вооружений, оно – на пределе возможного.

Все попытки частичных реформ – а их было немало – терпели неудачу одна за другой. Страна теряла перспективу. Так дальше жить было нельзя. Надо было кардинально все менять.

Вот почему я ни разу не пожалел, что не воспользовался должностью Генерального секретаря только для того, чтобы „поцарствовать“ несколько лет. Считал бы это безответственным и аморальным.

Я понимал, что начинать реформы такого масштаба и в таком обществе, как наше, – труднейшее и даже рискованное дело. Но и сегодня я убежден в исторической правоте демократических реформ, которые начаты весной 1985 года.

Процесс обновления страны и коренных перемен в мировом сообществе оказался куда более сложным, чем можно было предположить. Однако то, что сделано, должно быть оценено по достоинству:

– Общество получило свободу, раскрепостилось политически и духовно. И это – самое главное завоевание, которое мы до конца еще не осознали, а потому, что еще не научились пользоваться свободой. Тем не менее, проделана работа исторической значимости:

– Ликвидирована тоталитарная система, лишившая страну возможности давно стать благополучной и процветающей.

– Совершен прорыв на пути демократических преобразований. Реальными стали свободные выборы, свобода печати, религиозные свободы, представительные органы власти, многопартийность. Права человека признаны как высший принцип.

– Началось движение к многоукладной экономике, утверждается равноправие всех форм собственности. В рамках земельной реформы стало возрождаться крестьянство, появилось фермерство, миллионы гектаров земли отдаются сельским жителям, горожанам. Узаконена экономическая свобода производителя, и начали набирать силу предпринимательство, акционирование, приватизация.

– Поворачивая экономику к рынку, важно помнить – делается это ради человека. В это трудное время все должно быть сделано для его социальной защиты, особенно это касается стариков и детей.

Мы живем в новом мире. – Покончено с „холодной войной“, остановлена гонка вооружений и безумная милитаризация страны, изуродовавшая нашу экономику, общественное сознание и мораль. Снята угроза мировой войны.

Еще раз хочу подчеркнуть, что в переходный период с моей стороны было сделано все для сохранения надежного контроля над ядерным оружием.

– Мы открылись миру, отказались от вмешательства в чужие дела, от использования войск за пределами страны. И нам ответили доверием, солидарностью и уважением.

– Мы стали одним из главных оплотов по переустройству современной цивилизации на мирных, демократических началах.

– Народы, нации получили реальную свободу выбора пути своего самоопределения. Поиски демократического реформирования многонационального государства вывели нас к порогу заключения нового Союзного договора.

Все эти изменения потребовали огромного напряжения, проходили в острой борьбе, при нарастающем сопротивлении сил старого, отжившего, реакционного – и прежних партийно-государственных структур, и хозяйственного аппарата, да и наших привычек, идеологических предрассудков, уравнительной и иждивенческой психологии. Они наталкивались на нашу нетерпимость, низкий уровень политической культуры, боязнь перемен. Вот почему мы потеряли много времени. Старая система рухнула до того, как успела заработать новая. И кризис общества еще больше обострился.

Я знаю о недовольстве нынешней тяжелой ситуацией, об острой критике властей на всех уровнях и лично моей деятельности. Но еще раз хотел бы подчеркнуть: кардинальные перемены в такой огромной стране, да еще с таким наследием, не могут пройти безболезненно, без трудностей и потрясений.

Августовский путч довел общий кризис до предельной черты. Самое губительное в этом кризисе – распад государственности. И сегодня меня тревожит потеря нашими людьми гражданства великой страны – последствия могут оказаться очень тяжелыми для всех.

Жизненно важным мне представляется сохранить демократические завоевания последних лет. Они выстраданы всей нашей историей, нашим трагическим опытом. От них нельзя отказываться ни при каких обстоятельствах и ни под каким предлогом. В противном случае все надежды на лучшее будут похоронены.

Обо всем этом я говорю честно и прямо. Это мой моральный долг.

Сегодня хочу выразить признательность всем гражданам, которые поддержали политику обновления страны, включились в осуществление демократических реформ.

Я благодарен государственным, политическим и общественным деятелям, миллионам людей за рубежом – тем, кто понял наши замыслы, поддержал их, пошел нам навстречу, на искреннее сотрудничество с нами.

Я покидаю свой пост с тревогой. Но и с надеждой, с верой в вас, в вашу мудрость и силу духа. Мы – наследники великой цивилизации, и сейчас от всех и каждого зависит, чтобы она возродилась к новой современной и достойной жизни.

Хочу от всей души поблагодарить тех, кто в эти годы вместе со мной стоял за правое и доброе дело. Наверняка каких-то ошибок можно было бы избежать, многое сделать лучше. Но я уверен, что раньше или позже наши общие усилия дадут плоды, наши народы будут жить в процветающем и демократическом обществе.

Желаю всем вам всего самого доброго».

English translation:

“Dear compatriots, fellow citizens!

In light of the situation which has developed with the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States, I am ceasing my activity in the post of President of the USSR. I take this decision for reasons of principle.

I have firmly stood for the independence and self-rule of peoples, for the sovereignty of the republics. But at the same time, I have fought to preserve the union state and the country’s unity.

Events have taken a different course. The policy of dismembering the country and disuniting the state has prevailed – something I cannot agree with. Even after the Alma-Ata meeting and the decisions taken there, my stance on this issue has not changed.

Moreover, I am convinced that decisions of such magnitude should have been made on the basis of a popular expression of will.

Nevertheless, I will do everything in my power to ensure that the agreements signed there lead to genuine accord in society and facilitate the way out of the crisis and the continuation of reforms.

Addressing you for the last time as President of the USSR, I find it necessary to share my assessment of the path we have traveled since 1985 – especially since there are many contradictory, superficial, and unfair judgments on this subject.

Fate willed that when I found myself at the helm of the state, it was already clear that something was wrong in the country. We had plenty of everything – land, oil and gas, other natural riches, and God endowed us with intelligence and talent – yet we lived much worse than the developed countries, falling further and further behind them.

The reason was already evident: society was suffocating under the grip of the command-bureaucratic system. Condemned to serve ideology and carry the terrible burden of the arms race, it had reached the limits of its capacity.

All attempts at partial reform – and there were many – failed one after another. The country was losing perspective. We could not go on living like that. Everything had to be changed radically.

That is why I have never for a moment regretted that I did not use my position as General Secretary merely to “reign” for a few years. I would have considered that irresponsible and immoral.

I understood that initiating reforms of such scale in a society like ours was an extremely difficult and even risky undertaking. But even today I am convinced of the historical rightness of the democratic reforms that were begun in the spring of 1985.

The process of renewing the country and of profound changes in the world community turned out to be far more complex than could be anticipated. However, what has been accomplished should be given its due:

– Society has obtained freedom; it has been liberated politically and spiritually. This is the most important achievement, one we have not yet fully grasped because we have not yet learned how to use freedom. Nonetheless, work of historic significance has been done:

– The totalitarian system, which had long deprived the country of the opportunity to become prosperous and affluent, has been eliminated.

– A breakthrough has been achieved on the road to democratic transformation. Free elections, freedom of the press, religious freedoms, representative bodies of power, multi-partisanship – all have become realities. Human rights have been recognized as the highest principle.

– Movement toward a diversified economy has begun, and the equality of all forms of ownership is being affirmed. As part of land reform, the peasantry has begun to revive; private farming has appeared; millions of hectares of land are being given to rural and urban people. Economic freedom for the producer has been legalized, and entrepreneurship, joint-stock companies, and privatization have gained momentum.

– In turning the economy toward the market, it is important to remember that this is being done for the sake of the people. In this difficult time, everything must be done to protect the social well-being of the people – especially the elderly and children.

We are living in a new world. The “Cold War” is over; the arms race has been stopped, as has the insane militarization of the country that had distorted our economy, public consciousness, and morals. The threat of world war has been lifted.

I want to emphasize again that, during this transition period, everything necessary was done on my part to maintain reliable control over nuclear weapons.

– We have opened up to the world, renounced interference in others’ affairs, and renounced the use of troops outside our country. And in response, we have been met with trust, solidarity, and respect.

– We have become one of the main pillars in the restructuring of modern civilization on peaceful, democratic foundations.

– Peoples and nations have obtained a real freedom to choose the path of their self-determination. The search for a democratic reform of our multi-national state had brought us to the threshold of signing a new Union Treaty.

All these changes demanded immense exertion; they took place in sharp struggle, amid growing resistance from the old, obsolete, reactionary forces – from the former party-state structures and the economic apparatus, and also from our own habits, ideological prejudices, and leveling, dependent mentality. They encountered our intolerance, our low level of political culture, our fear of change. That is why we lost a lot of time. The old system collapsed before the new one had time to begin functioning, and the crisis in society grew even more acute.

I am aware of the dissatisfaction with the current grave situation, the sharp criticism of the authorities at all levels and of my own actions. But once again I want to stress: radical changes in such a vast country, especially given its legacy, cannot occur painlessly, without difficulties and upheavals.

The August coup brought the general crisis to its ultimate limit. The most devastating aspect of this crisis is the disintegration of statehood. And today I am troubled by the fact that our people have lost the citizenship of a great country – the consequences could be very grave for everyone.

I consider it vitally important to preserve the democratic achievements of recent years. They have been paid for through all our history and our tragic experience. We must not abandon them under any circumstances or pretexts; otherwise all our hopes for a better future will be buried.

I speak of all this honestly and directly. It is my moral duty.

Today, I would like to express my gratitude to all the citizens who supported the policy of renewing the country, who got involved in implementing the democratic reforms.

I am grateful to the statesmen, political and public figures, and to millions of people abroad – to all those who understood our aspirations, supported them, and came to meet us in sincere cooperation.

I leave my post with concern, but also with hope, with faith in you, in your wisdom and strength of spirit. We are the heirs of a great civilization, and now the revival of that civilization to a new, modern and dignified life depends on each and every one of us.

I want to thank from the bottom of my heart those who, over these years, stood with me for what is right and good. Certainly, some mistakes could have been avoided and many things could have been done better. But I am convinced that, sooner or later, our common efforts will yield fruit, and our peoples will live in a prosperous and democratic society.

I wish all the best to all of you.” [rbth.com]

Conclusion. The end of the Soviet Union, formalized by Gorbachev’s announcement on December 25, 1991, remains one of the pivotal events of the 20th century. In a few months, a chapter that had lasted seventy years was closed, and another opened, filled with uncertainties. For enthusiasts of Russian and Soviet horology, that moment was also a dividing line between two eras in manufacturing: the watch factories of the former USSR suddenly had to face a new reality on their own – some shut down or transformed, while others found ways to survive and continue their proud tradition (for instance, the First Moscow Watch Factory – Poljot – was privatized in the 1990s; the Raketa factory in Saint Petersburg sought out new markets, etc.). On the broader historical level, the dissolution of the USSR occurred in a relatively orderly and peaceful manner – a result that was by no means guaranteed, made possible by both the sense of responsibility of leaders like Gorbachev (who refused to use force to hold together an empire that was falling apart) and by the willingness of the republics to cooperate, at least to some extent, within the CIS to avoid total chaos. Although the CIS did not achieve the integration that had been hoped for, that exit of the Soviet Union stands as an example of a tectonic transition managed without sliding into civil war among the former compatriots.

Thirty years later, history books offer varying judgments on the protagonists of those days – Gorbachev revered by some as the architect of freedom, criticized by others as the one who “lost the Empire” – but the importance of understanding the events of 1989–1991 is beyond dispute. We hope this article, rich in documented details and primary sources, provides a useful and authoritative resource for those who wish to delve into that crucial period, which truly was a turning point for Russia, Europe, and the entire world. [en.wikipedia.org]