Introduction

In the late 1980s, during the Perestroika period, the Peterhof Watch Factory saw the emergence of several cooperatives, including the renowned “Peterhof Masters”. One of their most iconic creations is the Raketa watch commemorating the nuclear icebreaker “Yamal”. This article explores the distinctive features of this rare watch, highlighting its design and the historical context in which it was produced.

Description of the Raketa Yamal Watch

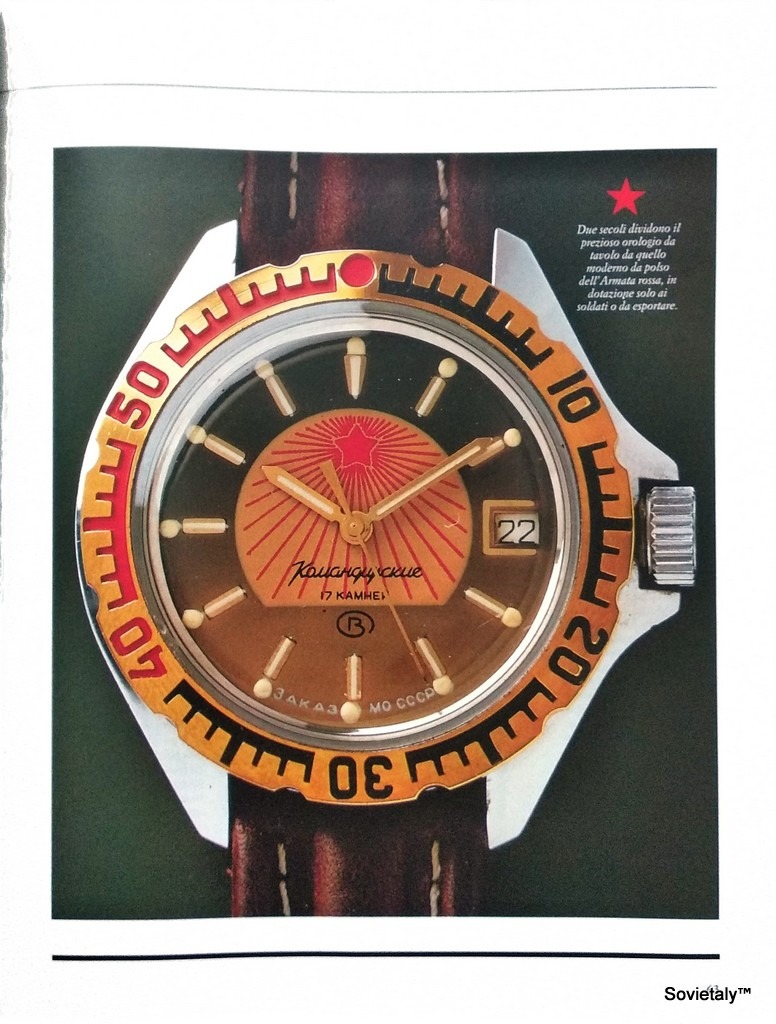

The Raketa Yamal watch boasts several distinctive elements:

- Case: Made of gold-plated brass with a TiN-finished bezel, measuring approximately 36 mm in diameter.

- Dial: The dial features a detailed print of the nuclear icebreaker Yamal. It is signed “P.M.” (Peterhof Masters). Within the image, the initials “A.L.M.” (Atomnyy Ledomkol Yamal) are part of the commemorative illustration. The blue lines at the top of the dial represent a stylized aurora borealis, a typical graphic element of polar watches. This design predates the addition of the famous shark mouth painted on the ship’s hull in the 1990s.

- Hands: Black dagger-shaped hands, including the second hand.

- Movement: Equipped with a mechanical 2614 movement from a Russian factory, with an unengraved bridge, marked “2614” and the “Angels” logo.

- Case Back: Pressure-fitted steel case back without inscriptions.

The video presents a rare watch from the late 1980s called the Atomic Icebreaker Yamal, produced by the Peterhof Masters cooperative. The watch is distinguished by its dial printed with the image of the Yamal atomic icebreaker and the date at 6 o’clock, signed “П.М.” (Peterhof Masters) and “АЛМ” (Atomic Icebreaker Yamal). Classic baton hands for hours and minutes and a red seconds hand complete the design. The chrome-plated brass case with a smooth finish, the plexiglass crystal and the black leather strap give the watch an elegant and robust appearance. The snap-back case back hides a late-model Russian 2614 mechanical movement, with a flat mainspring, shock absorber under the anchor and balance wheel without a regulating screw. A rare and fascinating watch, which captures attention for its unique design and its history linked to the late 1980s and the Peterhof Masters cooperative. A true collector’s item for fans of vintage watches and Russian history.

The Peterhof Watch Factory Cooperatives

During Perestroika, the historic Peterhof Watch Factory, also known as Raketa, gave rise to three unique cooperatives: Renaissance, Prestige, and Peterhof Masters. These cooperatives represent a fascinating chapter in Soviet watch history, characterized by high quality and innovative designs.

- Renaissance: Specialized in watches with semi-precious stone dials like jade, jasper, malachite, and nephrite.

- Prestige: Known for its mirror dials with religious themes and images of churches.

- Peterhof Masters: Focused on producing watches with printed dials on various themes, often decorated with high-quality naval and military images. The commemorative Yamal watch is one of their most iconic models.

The Yamal Icebreaker

The Yamal is one of the nuclear icebreakers of the Arktika class, built to operate in harsh Arctic conditions. Here are some of its main technical characteristics:

- Nuclear Reactors: Equipped with two OK-900A nuclear reactors, each with a capacity of 171 MW, for a total thermal power of 342 MW.

- Power: The maximum propulsion power is 75,000 horsepower (approximately 55.3 MW), distributed over three four-blade propellers, each 5.7 meters in diameter.

- Dimensions: Length of 148 meters, width of 30 meters, draft of 11.08 meters, height from keel to masthead of 55 meters.

- Displacement: 23,455 tons.

- Speed: Maximum speed in open water of 22 knots (about 40 km/h) and the ability to break ice up to 2.3 meters thick at a speed of 3 knots (about 5.5 km/h).

- Hull Structure: The outer hull is 48 mm thick in areas in contact with ice and 25 mm elsewhere, with a polymer coating to reduce friction. It uses an air and hot water bubble system to facilitate icebreaking.

The Yamal is known for its ability to navigate through thick Arctic ice, thanks to its powerful nuclear reactors and advanced icebreaking technologies. It has played a significant role in creating annual travel expeditions to the North Pole, being one of the few ships capable of reaching this destination and safely transporting tourists (CruiseMapper) (Wikipedia).

Tourist Cruises

The Yamal offers tourist cruises to the North Pole, a unique experience for adventurers. These cruises typically depart from Murmansk, Russia, and prices for a 14-day cruise can be around $30,000 per person. The cruises include various activities such as helicopter tours, Zodiac excursions, and photography programs (Poseidon Expeditions) (Cruise Critic).

Conclusion

The Raketa Yamal watch by the Peterhof Masters cooperative is a rare and valuable piece for collectors and watch enthusiasts. It represents not only the excellence of Soviet craftsmanship but also an era of change and innovation. For more details and an in-depth look at the watch, you can consult Dmitry Brodnikovskiy’s video available on YouTube, which provides a detailed analysis of this unique model.

Sources

- Wikipedia: Petrodvorets Watch Factory

- Watches of the USSR

- The Watch Cooperatives of the Petrodvorets Factory – Sovietaly

- CruiseMapper: Yamal icebreaker

- Poseidon Expeditions: North Pole expedition

- CruiseCritic: North Pole Cruises

- Orologio Raketa Rompighiaccio Atomico Yamal (sovietaly.blogspot.com)

- Raketa Big Zero: The Story Behind One of the Most Iconic Watches

- CCCP Sputnik 1 – A Watch That Celebrates the Space Age

- How to Remove Scratches from the Plexiglass of Your Watch: Complete Guide

- Complete Guide to Modern Russian Watchmaking

- Soviet CCCP Watch: The History of SOVIET Watches from the ’90s

- Russian Military Watches: A Comprehensive Guide