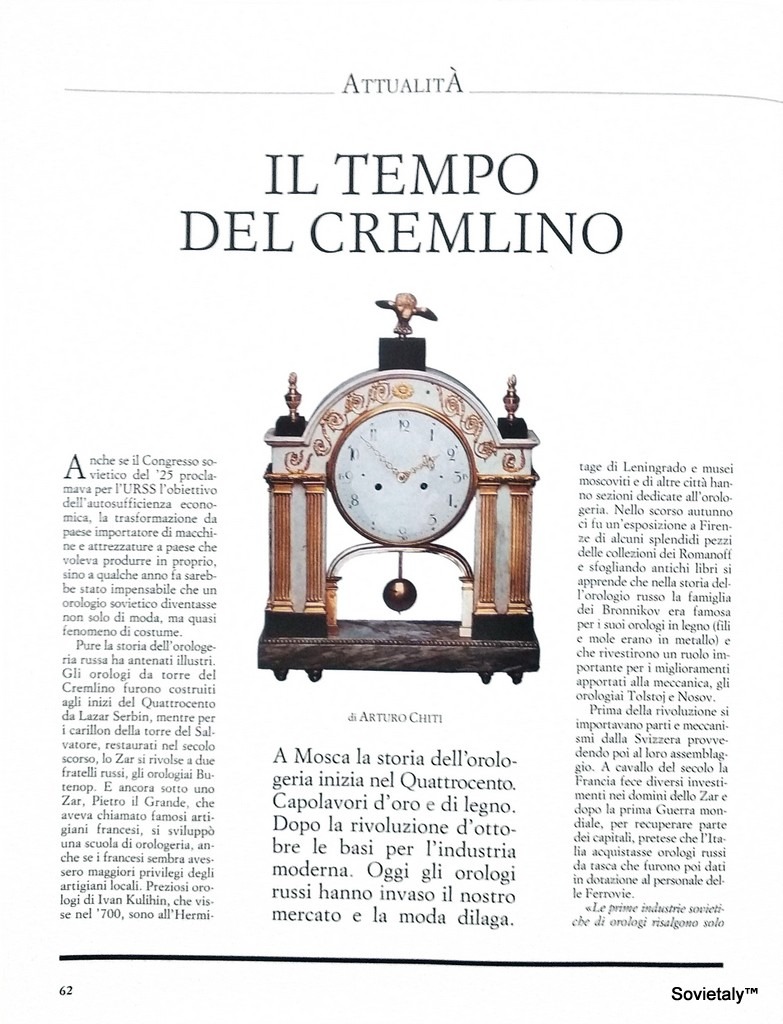

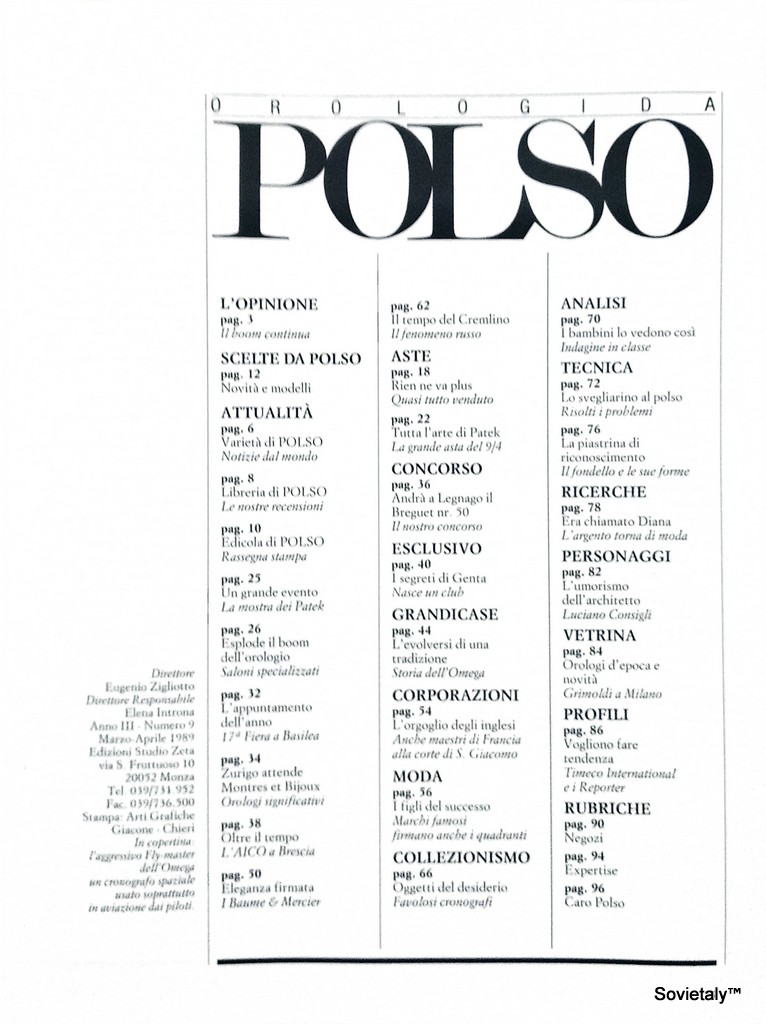

I recently recovered a copy of “Orologi da Polso” Year III no. 9 (March–April 1989, Edizioni Studio Zeta, Monza), an influential Italian magazine dedicated to horology during the late-1980s Soviet watch boom.

Inside, you’ll find an insightful article by Arturo Chiti, full of details about Soviet watchmaking, Italy’s first Russian watch importers, and a unique perspective on the Italian watch scene during the era of Gorbachev.

Below is the original article in Italian, followed by an English translation, to preserve and share this important piece of watch history with an international audience.

Testo originale – Italiano

Anche se il Congresso sovietico del ’25 proclamava per l’URSS l’obiettivo dell’autosufficienza economica, la trasformazione da paese importatore di macchine e attrezzature a paese che voleva produrre in proprio, sino a qualche anno fa sarebbe stato impensabile che un orologio sovietico diventasse non solo di moda, ma quasi fenomeno di costume.

Pure la storia dell’orologeria russa ha antenati illustri. Gli orologi da torre del Cremlino furono costruiti agli inizi del Quattrocento da Lazar Serbin, mentre per i carillon della torre del Salvatore, restaurati nel secolo scorso, lo Zar si rivolse a due fratelli russi, gli orologiai Butenop. E ancora sotto uno Zar, Pietro il Grande, che aveva chiamato famosi artigiani francesi, si sviluppò una scuola di orologeria, anche se i francesi sembra avessero maggiori privilegi degli artigiani locali. Preziosi orologi di Ivan Kulihin, che visse nel ‘700, sono all’Hermitage di Leningrado e musei moscoviti e di altre città hanno sezioni dedicate all’orologeria. Nello scorso autunno ci fu un’esposizione a Firenze di alcuni splendidi pezzi delle collezioni dei Romanoff e sfogliando antichi libri si apprende che nella storia dell’orologio russo la famiglia dei Bronnikov era famosa per i suoi orologi in legno (filie molle erano in metallo) e che rivestirono un ruolo importante per i miglioramenti apportati alla meccanica, gli orologiai Tolstoj e Nosov.

Prima della rivoluzione si importavano parti e meccanismi dalla Svizzera provvedendo poi al loro assemblaggio. A cavallo del secolo la Francia fece diversi investimenti nei domini dello Zar e dopo la prima Guerra mondiale, per recuperare parte dei capitali, pretese che l’Italia acquistasse orologi russi da tasca che furono poi dati in dotazione al personale delle Ferrovie.

«Le prime industrie sovietiche di orologi risalgono solo agli anni Trenta» dice Jacopo Marchi, P.R. dell’Artime, che è andato a Mosca nello scorso dicembre dopo che l’azienda napoletana aveva sottoscritto un accordo di collaborazione con la Boctok (ma si legge Vostok). Dal viaggio in Russia Marchi ha riportato molte notizie, tanto che per il lancio dei «Komandirskie» ha realizzato per Time Trend, distributore del prodotto, un tabloide sulla storia dell’Armata rossa e dei suoi orologi.

Due industrie (una di orologi preziosi e l’altra di orologi con casse di legno) vennero convertite in aziende belliche negli anni ’40, per tornare poi alle funzioni originali. L’industria principale di Mosca diede vita nel ’42 alla Boctok, una delle più importanti e tra le poche di cui per le strade moscovite si possono vedere cartelloni pubblicitari. Dopo la fine della guerra altre industrie furono aperte a Serdobsk, Yerevan, Petrodvoretes e Uglich. Venne creato un istituto per la ricerca e il design nelle lavorazioni meccaniche. Nel 1962 furono anche prodotti i primi orologi a diapason.

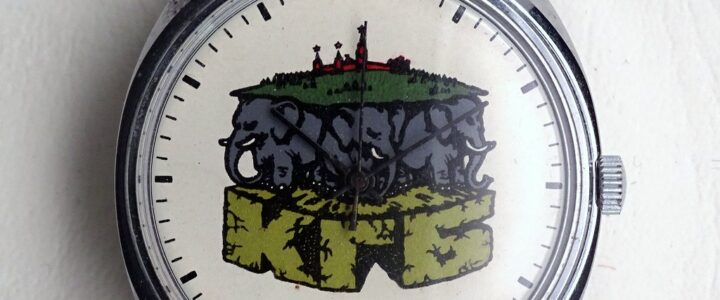

Oggi in URSS operano oltre quindici fabbriche di orologi, molte delle quali specializzate in produzioni particolari. Tra le più note ricordiamo Chaika, Poljot, Zaria, Paketa, Slava e Penza, quest’ultima destinata alla produzione di orologi da polso femminili. Il quantitativo di orologi prodotti è imponente. Intorno agli anni Cinquanta iniziò anche l’esportazione destinata per lo più a nazioni aderenti al patto di Varsavia. Erano orologi di buon livello con prezzi politicamente differenziati. È di quegli anni il Mark che pubblichiamo e il cui quadrante è simile a quello del Poljot. È un orologio con una storia romantica. Fu donato a un nostro collega, allora bambino, da una signora italiana che aveva sposato un russo che, per le leggi staliniane, non poteva venire a vivere in Italia e i due erano costretti così a vedersi di tanto in tanto solo come turisti.

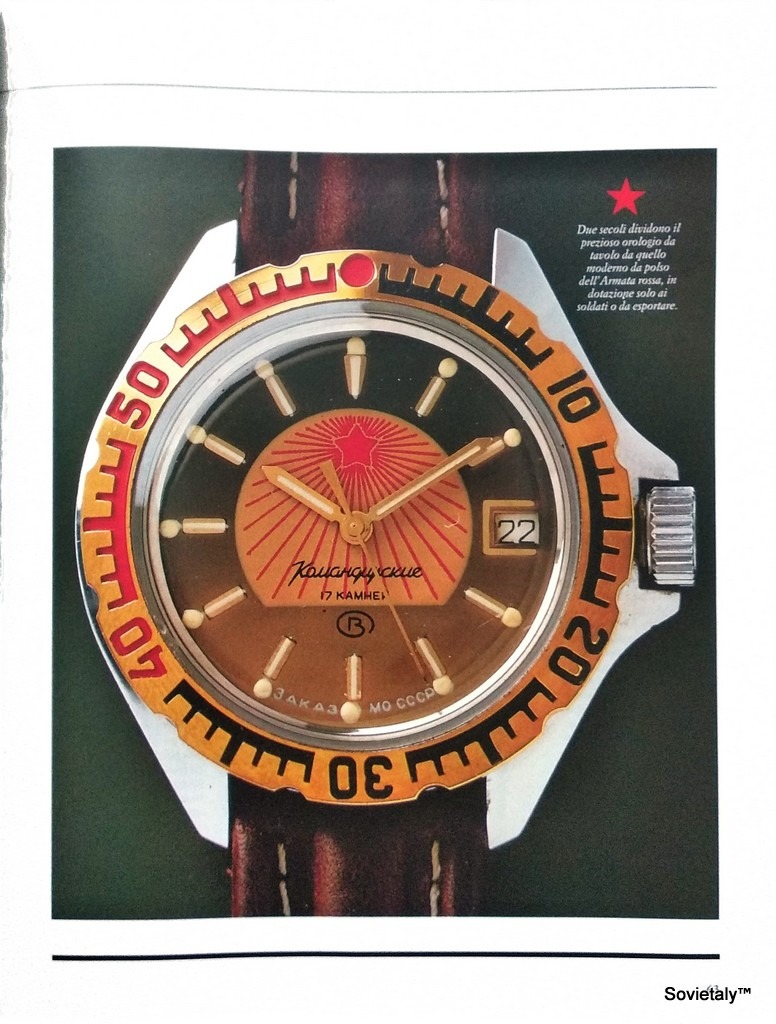

La prima importazione di orologi russi in Italia è stata fatta da Orazio Occhipinti della Mirabilia di Milano che nella seconda metà del 1988 ha iniziato sul territorio nazionale la distribuzione dei Paketa fabbricati a Pietrogrado. Paketa in russo significa «razzo» e si legge «raketa», La bontà dell’idea, complice anche l’apertura generale verso Gorbaciov, è stata ampiamente confermata dalla vera e propria corsa all’orologio russo che si è scatenata in seguito. Vien da pensare a questo proposito che solo pochi anni or sono un dirigente di una grande azienda europea, dopo un viaggio in Unione Sovietica durante il quale era rimasto colpito dagli orologi, ne propose l’importazione ma si sentì chiedere dai suoi se aveva voglía di scherzare. Dunque i primi russi che hanno rotto il ghiaccio sul nostro mercato sono stati i Paketa. Oggi sono disponibili nove versioni che si differenziano sia per il design del quadrante per le funzioni. Sono meccanici a carica manuale e cassa antishock. Alla fiera di Vicenza Mirabilia ha presentato anche i Poljot prodotti a Leningrado, un cronografo e uno svegliarino, a carica manuale, proposti in quattro versioni. Gli orologi dell’Armata rossa, i Boctok, sono disponibili in cinque modelli con quadranti realizzati per le specializzazioni dell’esercito al quale sono destinati. Sono orologi meccanici a carica manuale, impermeabili a 10 atmosfere, hanno la ghiera girevole con indici e lancette fosforescenti.

Ci sono poi orologi con meccanismo di fabbricazione russa e cassa e quadrante costruiti in Italia per accostare un «cuore» russo al design italiano, come il Soviet, disponibile in vari colori di cassa e quadrante. È un orologio quarzo impermeabile a 3 atm. E ancora i sei modelli della collezione Perestrojka (quattro al quarzo e due cronografi meccanici) che la Elmitex ha presentato sia a Vicenza sia a Mosca come un prodotto «italorusso».

Il sesto orologio con la stella rossa è quello proposto dalla I. Binda S.p.A. Il marchio BREMA, con la A che è una R rovesciata, si legge Vremia e significa Tempo. Sono orologi meccanici disponibili in tre modelli (normale, con suoneria e un cronografo) proposti in 17 versioni. I quadranti sono di ispirazione anni ’30 seguendo la tendenza culturale in voga in Russia e battezzata «strutturalista».

Full English Translation

Even though the 1925 Soviet Congress declared the USSR’s goal of economic self-sufficiency, turning the country from an importer of machinery and equipment into a producer, until just a few years ago it would have been unthinkable for a Soviet wristwatch to become not only fashionable, but a genuine social phenomenon.

Russian watchmaking, however, has illustrious origins. The Kremlin’s tower clocks were built in the early 15th century by Lazar Serbin, and when the chimes of the Saviour Tower were restored last century, the Tsar turned to two Russian brothers, the Butenops, who were master clockmakers. Under Peter the Great, who invited famous French craftsmen to Russia, a Russian watchmaking school developed—even if the French apparently enjoyed more privileges than the local artisans. Precious watches by Ivan Kulikhin, who lived in the 18th century, can be found at the Hermitage in Leningrad, and museums in Moscow and other cities have sections devoted to horology. Last autumn, a Florence exhibition featured stunning pieces from the Romanoff collections. Old books reveal that the Bronnikov family was famous for its wooden watches (with metal gears), and that watchmakers like Tolstoy and Nosov played a key role in technical improvements.

Before the Revolution, parts and movements were imported from Switzerland and assembled locally. At the turn of the century, France invested in the Tsar’s domains, and after the First World War—seeking to recover capital—demanded that Italy purchase Russian pocket watches, which were later issued to Italian railway workers.

“The first Soviet watch factories date only to the 1930s,” says Jacopo Marchi, PR manager for Artime, who travelled to Moscow last December after the Neapolitan company signed a collaboration agreement with Boctok (pronounced Vostok). Marchi brought back a wealth of information, so much so that for the launch of the ‘Komandirskie’ he produced a special magazine on the Red Army and its watches for Time Trend, the product’s Italian distributor.

Two factories—one producing luxury watches, the other making wooden-cased watches—were converted to wartime production in the 1940s, only to return to their original functions later. Moscow’s main factory gave rise in 1942 to Boctok, one of the most important Soviet brands, and among the few to have billboards in Moscow’s streets. After the war, new factories opened in Serdobsk, Yerevan, Petrodvorets and Uglich. An institute for mechanical research and design was founded. In 1962, the first Soviet tuning fork (diapason) watches were made.

Today, more than fifteen watch factories operate in the USSR, many specialising in particular types of production. The best known include Chaika, Poljot, Zaria, Paketa, Slava and Penza, the latter focusing on women’s wristwatches. The number of watches produced is enormous. From the 1950s, Soviet watches were exported mainly to other Warsaw Pact nations—well-made pieces, with politically adjusted pricing. One such watch, the Mark (with a dial similar to the Poljot) is featured here. It has a romantic history: it was given to a colleague, then a child, by an Italian woman who had married a Russian. Under Stalinist law, he was not allowed to live in Italy, so the couple could only meet occasionally as tourists.

The first import of Russian watches to Italy was by Orazio Occhipinti of Mirabilia (Milan), who began national distribution of Paketa watches from Petrograd in the second half of 1988. Paketa in Russian means “rocket” and is pronounced “Raketa.” The idea’s success—helped by the general mood of openness under Gorbachev—was clear from the sudden rush for Russian watches that followed. Interestingly, only a few years earlier, an executive at a major European firm, after visiting the USSR and being struck by the watches, suggested importing them—only to be asked if he was joking. So, Paketa were the first to break the ice in our market. Today, there are nine available versions, differing in dial design and function. They are manual-wind mechanicals with anti-shock cases. At the Vicenza fair, Mirabilia also presented Poljot watches made in Leningrad—a chronograph and an alarm watch, both manual-wind, offered in four versions. Red Army watches—Boctok—come in five models, each with dials themed for army specialisations. These are manual-wind mechanical watches, water resistant to 10 atmospheres, with rotating bezels and luminous hands and markers.

There are also watches with Russian-made movements, but Italian cases and dials, to combine a Russian “heart” with Italian design—such as the Soviet, available in a range of case and dial colours. This is a quartz watch, water resistant to 3 atm. Then there are six models in the Perestrojka collection (four quartz, two mechanical chronographs) presented by Elmitex at both Vicenza and Moscow as an “Italo-Russian” product.

The sixth red-star watch is offered by I. Binda S.p.A. The BREMA brand—with a reversed R for the “A”—is read as Vremia, meaning Time. These are mechanical watches available in three models (standard, alarm, and chronograph) with 17 dial versions. The dials are inspired by the 1930s, in keeping with a cultural trend currently popular in Russia, known as “structuralist.”

Conclusion

This rare 1989 issue of Orologi da Polso is a true time capsule for any vintage or Soviet watch collector. The article not only chronicles the arrival of Russian watches in Italy but also captures the atmosphere, tastes, and market dynamics of the era. Whether you’re passionate about Vostok, Raketa, Poljot, or the unique East-West collaborations, this publication is a valuable reference and a fascinating read for enthusiasts everywhere.

If you have memories or stories related to Orologi da Polso or the Russian watch craze in Italy, share them below or get in touc