Introduction

Steel has long been the material of choice in watchmaking, especially for cases and bracelets. Its popularity comes from its corrosion resistance, robustness, and relatively low cost compared to precious metals. This article takes a deep dive into the different types of stainless steel used in watches—from the ubiquitous 316L to the more exclusive 904L—focusing especially on Soviet and Russian steels found in both vintage and modern models. We will explore the technical properties (corrosion, hardness, workability), how they affect design and longevity, and compare them with those used by Swiss (Rolex, Omega), Japanese (Seiko, Citizen), American, and Italian manufacturers. The tone is midway between technical and enthusiast, and we include data, real-world examples, and references to metallurgical standards such as GOST, where possible.

Types of Stainless Steel in Watchmaking

Quality watches almost exclusively use austenitic stainless steels, which contain a high proportion of chromium and nickel. This creates a passive surface layer, protecting against rust. The most common alloys are:

- AISI 304 – Also known as 18/8 (about 18% Cr, 8% Ni), 304 is widely used in everyday objects (cutlery, kitchenware, etc.). In watchmaking, it appears in cases and bracelets of entry-level and mid-range timepieces. Its corrosion resistance is decent in regular environments, though it lacks molybdenum, which improves performance in marine settings. Thus, a 304 steel watch can withstand salt water and chlorine but should be rinsed after immersion. It is easier to machine than higher grades, resulting in lower production costs and a slightly darker finish compared to 316L. This makes it ideal for high-volume, affordable models.

- AISI 316L – Known as surgical steel or marine steel, 316L is the industry standard for quality watches. With about 17% Cr, 12% Ni, and 2-2.5% Mo, it boasts outstanding resistance to corrosion, especially in salty or humid conditions. The “L” denotes a low carbon content (≤0.03%), minimising intergranular corrosion (notably important for welds, even if seldom used in watch cases). 316L strikes a near-perfect balance: highly rust-resistant, hypoallergenic for most users, and tough enough to withstand bumps and scratches. As a result, the vast majority of steel watches use 316L, including those from leading Swiss, Japanese and international brands. It’s often marketed as “anti-corrosive” and “anti-magnetic” (the latter thanks to its austenitic structure).

- AISI 904L – This is a super-austenitic stainless steel with extremely high corrosion resistance, containing about 20-21% Cr, 25% Ni, and 4-5% Mo plus copper. In watchmaking, it’s best known for its use by Rolex: the brand switched from 316L to 904L in 1985, primarily for its sport models, to take advantage of its superior corrosion resistance and its highly lustrous finish. While 904L excels in harsh, acidic, or marine environments, the everyday user will see little difference versus 316L in ordinary conditions. It is somewhat softer than 316L, so while it polishes up beautifully, it can pick up light scratches more easily, though these are easy to remove due to the metal’s ductility. Note also the higher nickel content: 904L can be less suitable for those with nickel allergies.

- Other Steels – Beyond these three main types, a few other steel alloys have made appearances. In the early 20th century, Swiss brands developed and patented Staybrite, an early 18/8 stainless steel similar to 304, prized for its shine and corrosion resistance. Modern brands may use proprietary blends or special surface treatments: for example, Citizen’s Duratect hardening or Seiko’s Dia-Shield coatings to protect against scratches, or Sinn’s submarine steel with extra surface hardening. These are relatively rare; in reality, most watches use 304, 316L, or 904L (or close variants).

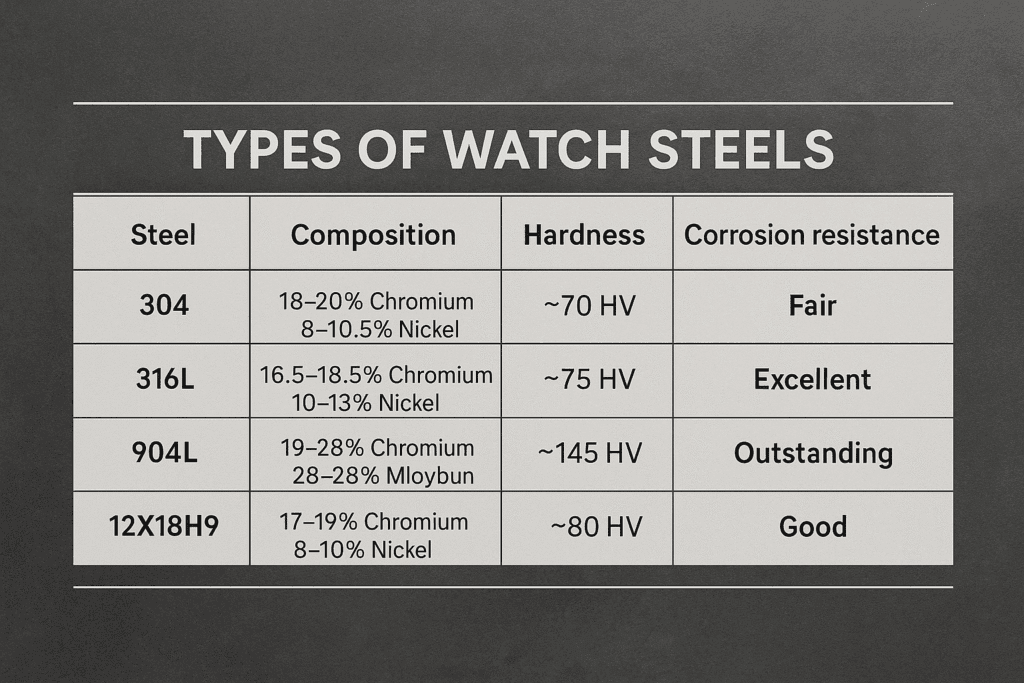

A comparative table of the most relevant steels:

| Alloy (Code) | Typical Composition | Hardness<br/>(approx.) | Corrosion Resistance | Use and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 (X5CrNi18-10) | ~18% Cr, 8% Ni, <0.08% C | ~70 HRB (150 HV) | Good in fresh water, less so in salt (no Mo) | Entry-level watches, historic “Staybrite”. Easy to machine. |

| 316L (X2CrNiMo17-12-2) | ~17% Cr, 12% Ni, 2% Mo, <0.03% C | ~95 HRB (170 HV) | Excellent in salt water, highly rust resistant | The global standard for quality watches; Swiss, Japanese, etc. |

| 904L (NW 1.4539) | ~20% Cr, 25% Ni, 4.5% Mo, ~1.5% Cu | ~90 HRB (160 HV) | Outstanding even in acidic or salty environments | Rolex’s “Oystersteel”; lustrous, anti-corrosive, expensive. |

| 12Х18Н9 (GOST USSR) | ~18% Cr, 9% Ni, ≤0.12% C (like 302/304) | ~70–80 HRB (est.) | Good; a bit lower than 316L (no Mo). Like AISI 304. | Used in Soviet/Russian cases from late ‘60s onwards. |

| Others (Duplex, etc.) | Proprietary (e.g. GS “Ever-Brilliant”) | ~95 HRB | Exceptionally high (PREN ~40, c. 1.7× 316L) | Rare, high-end use (e.g. Grand Seiko), bright white look. |

(Note: HRB = Rockwell B; HV = Vickers; PREN = Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number)

Soviet Watchmaking: From Brass to Steel

In the early decades of Soviet watchmaking (1930s–50s), stainless steel cases were unusual. Most watches were made from brass, sometimes chrome- or nickel-plated to mimic the look of steel or silver, or gold-plated for prestige models. This was partly due to ease of manufacturing, but also because top-quality steel was reserved for strategic industries. The move to stainless steel cases was slow and challenging, as forming and machining stainless required more advanced tools and know-how than most Soviet factories possessed in the post-war years.

Only from the mid-1960s onwards did things begin to change. Demand grew for more robust watches both domestically and for export, pushing Soviet factories to experiment with steel. In some instances, cases were initially made abroad or by partner countries, while local engineers worked to perfect their own production processes.

The First Soviet Steel Watches: Vostok Amphibia & Others

The turning point came in 1967 with the launch of the Vostok Amphibia, the first Soviet watch fully designed with a stainless steel case. A true diver, water-resistant to 200m, it was developed for both military and civilian use. Early models used an ingenious solution: detachable lugs (swing lugs) screwed onto the round case, as forming lugs in solid steel was a major technical hurdle at the time. Within a few years, the process improved, and by around 1970, integrated lugs became standard.

Through the 1970s and 80s, other Soviet brands followed suit—mainly for tool watches. But it’s important to stress: steel cases remained the exception. Most Soviet wristwatches for daily civilian use stuck with brass and plating, reserving steel for diving, military, and technical models. Notable examples beyond the Amphibia include:

- Raketa Amphibian – Raketa produced its own 200m dive watch in the 1970s, also with a steel case.

- Poljot/Okean Chronographs – High-grade steel cases for military chronographs, including those issued to the Soviet Navy.

- Sekonda De Luxe – Export models for the UK and other Western markets, sometimes made with steel cases for a premium feel.

- Sturmanskie and other military pieces – Certain pilot and cosmonaut watches used steel, especially for Western export or demanding roles, though the standard Komandirskie for internal use mostly stayed brass.

In summary, up to the end of the Soviet era, steel was used sparingly, mostly for tool and military watches—a fact that makes such models especially collectable today.

Soviet Steels: GOST Standards and Technical Details

Which steels were actually used? Soviet alloys followed GOST standards. The most common for watch cases was 12Х18Н9 (“12Kh18N9”), which closely matches AISI 304 in Western standards, albeit with slightly higher carbon for extra strength. Technical documents and modern Vostok factory listings confirm continued use of this alloy even today. Some references also mention 08Х18Н10, essentially the low-carbon 304L equivalent.

Key features of Soviet 12X18H9:

- Corrosion resistance: Far better than brass or carbon steel, and more than adequate for normal use, though not quite matching 316L in extreme marine settings due to lack of molybdenum. Soviet manuals always recommended rinsing watches after sea water exposure—a good practice with any steel.

- Workability and hardness: Easy to machine and form, well-suited to mass production with the Soviet Union’s mid-century technology. Somewhat softer than modern 316L, so Soviet steel cases could pick up scratches, but far less so than plated brass.

- Design impacts: Some design choices—such as the swing lugs on early Amphibias—were direct responses to the challenges of working steel. Otherwise, steel allowed for more robust, waterproof cases with tighter tolerances and improved sealing.

In summary, the move to stainless steel, though limited, was a significant leap for the Soviet industry. The shift from brass to steel enabled proper professional watches, especially for diving, military, and technical use, on par with Western rivals by the 1970s.

Russian Watches after the Soviet Era (1990s–Today)

After 1991, most Soviet-era factories either closed or dramatically downsized. Survivors like Vostok, Raketa, and a handful of Poljot descendants gradually adopted Western market standards—including materials. Thus, 316L became increasingly prevalent, especially for export models.

Modern Raketa timepieces are made from marine-grade 316L steel, often with scratch-resistant treatments. Vostok-Europe (a Lithuanian brand using Vostok movements) uses 316L for its divers, while Vostok Chistopol continues to make classic Amphibias in the traditional 12X18H9 alloy, alongside brass-cased models for lower-end lines like the Komandirskie.

A few Russian independents experiment with special steels (including damascus steel or titanium), but mainstream Russian watches today use the same materials as their global peers, namely 316L. Lower-cost models may still use brass cases with steel casebacks, a hybrid approach for cost-effectiveness—a strategy seen in low-cost watches worldwide.

Swiss Steels: From 316L to Oystersteel

Switzerland pioneered the use of stainless steel in watchmaking, especially with the Staybrite alloys of the 1930s. By the 1940s and 50s, nearly every Swiss brand had steel models. Early machining challenges were quickly overcome, and steel became “the precious metal of the masses” in the industry.

The Reign of 316L

From the 1950s to today, 316L has become the de facto standard for Swiss watch cases and bracelets (excluding precious metal pieces). Every leading Swiss manufacturer—Omega, TAG Heuer, Breitling, IWC, Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and so on—uses 316L for their steel models. Marketing from the 1990s onwards often called it “surgical steel”, referencing its hypoallergenic qualities and rust resistance.

The alloy is also ideal for finishing, allowing for crisp transitions between brushed and polished surfaces (as on the Royal Oak or Nautilus), and can be polished to a mirror shine with proper techniques. 316L is also widely considered hypoallergenic, thanks to its stable, low-nickel surface.

Rolex and 904L (Oystersteel)

Rolex is unique among major brands in having switched to 904L for all its steel watches, starting in 1985. Marketed as “Oystersteel”, this proprietary blend is extremely corrosion-resistant, especially in harsh, acidic, or marine environments. Rolex highlights its dazzling, almost platinum-like shine, attributed to its very high chromium content.

904L does pose production challenges: it is more expensive and harder to machine, and is slightly softer than 316L, meaning it scratches a bit more easily—though it can be polished back to a mirror shine with less effort. Its use is a mark of luxury and exclusivity, and its high cost is sustainable only at the top end of the market.

Other Swiss Innovations

While 316L dominates, the Swiss have innovated in finishing and case design as much as metallurgy. The original Audemars Piguet Royal Oak (1972) and Patek Philippe Nautilus made the steel sports watch a luxury icon, while brands like IWC have experimented with anti-magnetic cases (though this usually involves soft iron inner cases rather than special steels).

In short, most Swiss watches use 316L, with Rolex’s 904L as the main exception—ensuring a remarkably high and consistent standard for the consumer.

Japanese Steel: Seiko, Citizen and Innovation

Japanese brands became major watchmaking players from the 1960s onwards, adopting 316L and equivalent alloys early on. Seiko’s 1965 diver (6217 “62MAS”) was a landmark, and both Seiko and Citizen turned out millions of stainless steel watches in the decades that followed.

Japan stands out for material innovation:

- Grand Seiko “Zaratsu” – Grand Seiko is famed for its meticulous Zaratsu polishing, achieving dazzling mirror finishes on 316L steel, thanks in part to careful alloy selection for uniformity and absence of inclusions.

- Ever-Brilliant Steel – Since around 2020, Seiko and Grand Seiko have used “Ever-Brilliant Steel”, a proprietary alloy with a PREN (pitting resistance) about 1.7 times greater than 316L—making it possibly the most corrosion-resistant steel in watchmaking, and giving cases a bright, pure-white look.

- Citizen Duratect & Super Titanium – Citizen is known for advanced surface hardening (Duratect), producing steel watches with surface hardness far exceeding untreated steel, and for pioneering titanium cases, which are even more corrosion-resistant and hypoallergenic.

In mainstream Japanese watchmaking, 316L and 304 remain standard, but higher-end models showcase these innovations in both material and finishing.

American and Italian Steels

American watchmaking historically used brass and gold for civilian models, but military and technical watches often used stainless steel. The famous WWII “A-11” watches, for example, had robust steel cases. Modern American brands like Timex, Hamilton (now Swiss-owned), and microbrands mostly use 316L or rely on third-party manufacturers for cases. Some, like RGM, have experimented with damascus steel or reclaimed historic alloys for special editions.

Italy, despite its design heritage, sources its steels externally. Panerai, perhaps the most famous Italian brand, historically relied on Rolex for its steel cases and today uses 316L for most models, sometimes with proprietary treatments. Microbrands like Anonimo and U-Boat follow suit, prioritising bold design and finishing rather than unique alloys.

In both cases, it is finishing and style—not metallurgy—that sets these brands apart.

Performance, Cost and Aesthetics Compared

A quick summary:

- Corrosion resistance: 904L (and similar alloys like Ever-Brilliant) tops the charts, followed by 316L and then 304 or Soviet 12X18H9. For most users, all are sufficient for daily and even marine use, though rinsing after saltwater exposure is always recommended.

- Scratch resistance: 316L is slightly harder than 904L, but neither is immune to scratches. Treatments like Citizen’s Duratect or Seiko’s Dia-Shield improve this.

- Workability and cost: 304 is easiest and cheapest to machine; 316L requires more effort and tooling; 904L is the most demanding and expensive, and is mostly used by Rolex.

- Aesthetics: 904L polishes to a particularly bright, white finish, while 316L offers a classic, neutral steel look. These differences are subtle but can be noticed by connoisseurs.

- Weight: All austenitic steels are roughly equal in density, so there’s no real difference in feel.

- Magnetism: All are non-magnetic in their annealed state—ideal for watches.

The choice of steel is a balancing act: designers select the alloy that best matches their watch’s function and market position. Soviet tool watches, for example, made do with sturdy but cost-effective 304-type steel; modern Swiss, Japanese, American, and Italian watches almost always use 316L or better.

Conclusion

Steel revolutionised watchmaking, enabling robust, durable, and affordable timepieces. As seen in Soviet and Russian history, the transition from brass to steel unlocked new technical possibilities and greater reliability. Today, Russian watchmaking uses essentially the same steels as the rest of the world, with 316L the go-to for quality.

The global comparison shows near-universal adoption of the same alloys for reliability. Exceptions—Rolex with its 904L, Grand Seiko with Ever-Brilliant, a handful of high-tech treatments—serve as branding and technological differentiators, but for most users, the trusty 316L delivers superb performance at a fair price.

For watch enthusiasts, it is fascinating to realise that behind every steel case lies a world of metallurgy—alloys, international and Soviet standards, secrets of machining, and decades of technological evolution. This expertise makes the humble steel case not just a protective shell, but a monument to human ingenuity—a timepiece that defies the years with the strength of steel.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Types of Stainless Steel in Watchmaking

- 3 Soviet Watchmaking: From Brass to Steel

- 4 Russian Watches after the Soviet Era (1990s–Today)

- 5 Swiss Steels: From 316L to Oystersteel

- 6 Japanese Steel: Seiko, Citizen and Innovation

- 7 American and Italian Steels

- 8 Performance, Cost and Aesthetics Compared

- 9 Conclusion