This article aims to make valuable content, often inaccessible to non-native Russian speakers, readily available. We will be drawing from the insightful book “Московские часы” (Moscow Clocks), authored by B. Radchenko and published in Moscow by “Московский рабочий” (Moscow Worker) in 1980. This captivating volume serves as a guide, exploring the most intriguing timepieces located on buildings and structures across Moscow, as well as those exhibited in the capital’s museums. Let’s embark on this temporal journey together to uncover the rich heritage of Russian watches.

A Chronological Compendium of Russian Timepieces: Over Six Hundred Years of History

Radchenko’s book offers a comprehensive overview of the evolution of time-measuring instruments in Russia, from early rudimentary solutions to modern mass production.

- Introduction (Page 3): The text opens with Moscow’s ultimate symbol of time: the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower clock, whose chimes mark the day and the precise time for the nation. It highlights the remarkable progress of the Russian watchmaking industry, which, from being almost non-existent before the revolution, became capable of meeting domestic demand for high-quality timepieces.

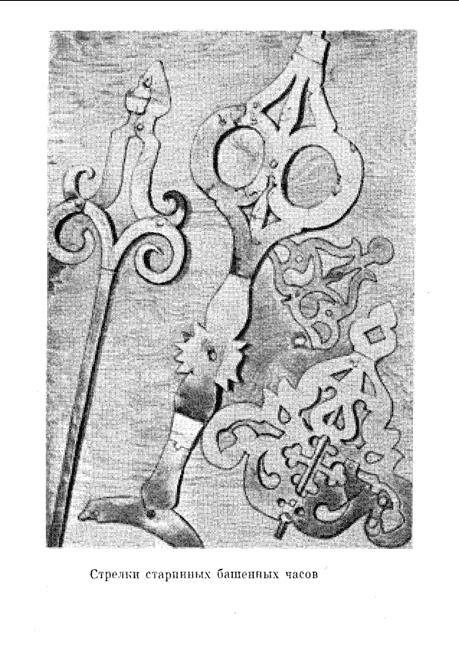

- Часы на башнях. Первые на Руси (Clocks on Towers. The First in Rus’) (Pages 4-16): This section takes us to the origins of Russian horology. In 1404, the Serbian monk Lazar installed the first tower clock in Moscow for Prince Vasily, a true marvel for its era that even showed moon phases. While chronicles don’t always identify the craftsmen, the emergence of other clocks in cities like Novgorod (1435) and Pskov (1476) is documented. The book describes the oldest surviving clocks, such as the Solovetsky Monastery clock (1539) by master Semyon Chasovik, an example of forged iron clockmaking. It also mentions clocks from the Pafnutiev-Borovsky Monastery (18th century) and the Kolomenskoye palace, including Pyotr Vysotsky’s (1673) with mechanised figures. Finally, a carillon clock by Ivan Yurina (1863) illustrates early factory productions with musical mechanisms.

- Кремлевские куранты (Kremlin Chimes) (Pages 17-26): This section is crucial for understanding the quintessential Russian timepiece. We will delve deeper into this part shortly.

- Часы столицы (Clocks of the Capital) (Pages 27-39): Beyond the Kremlin, Moscow boasts countless other public and tower Russian watches. The book takes us through the clocks of major railway stations (Kursky, Belorussky, Kiyevsky, etc.), many of which were modernised in the Soviet era, becoming landmarks and symbols of the stations themselves. It also discusses the clocks on the majestic Stalinist skyscrapers (the “Seven Sisters”), such as those of Moscow State University (MSU) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, noted for their imposing size. Mentions are also made of clocks on public and commercial buildings, like the GUM store clock in Red Square, and the timepiece of the renowned Bolshoi Theatre.

- В музеях Москвы (In Moscow’s Museums) (Pages 40-54): Moscow houses a rich collection of antique and rare Russian watches. The State Historical Museum displays table, pendulum, and pocket watches from the 17th-19th centuries, often of Russian production, true decorative art pieces with intricate inlays and enamels. The Polytechnic Museum, on the other hand, provides an overview of technological development, from early weight-driven clocks to modern chronometers. This section highlights the description of Ivan Kulibin’s astronomical clock (18th century), a masterpiece of precision and astronomical complexity.

- Наши дни (Our Days) (Pages 55-64): The final section focuses on the Soviet watchmaking industry and its success, which we will examine in more detail below.

In-Depth: The Iconic Kremlin Clock (Pages 17-26)

The Spasskaya Tower Clock, the beating heart of Moscow’s time, is far more than a mere mechanism. It is a silent witness to Russian history, and its evolution is a fascinating example of engineering and adaptation.

- After Lazar: Galloway’s Ornament (1625): The first significant clock on the Spasskaya Tower, following the 15th-century one, was installed in 1625. It was the work of the English master Christopher Galloway, who collaborated with the Russian Ivan Zharukhin. This timepiece was a true innovation: it featured a rotating dial with Arabic numerals and a fixed hand. The chimes struck the hours and quarter-hours, and, spectacularly, there were animated figures that appeared and disappeared, adding an element of wonder and entertainment.

- Peter the Great’s Modernisation (1705): Driven by Peter the Great’s push for Westernisation, Galloway’s clock was replaced in 1705 with a new mechanism imported from Holland. This marked the adoption of the more common design with a fixed dial and moving hands.

- Damage and Replacements (1737-1767): A devastating fire in 1737 damaged the clock, which was later repaired by the famous inventor I. Polzunov. Subsequently, in 1767, the Dutch mechanism was replaced with another from the Kremlin’s Palace of Facets, made by F.N. Polonsky in 1625, adapted with a specific musical chime.

- The Current Clocks: The Butenop Brothers’ Masterpiece (1848-1851): The Russian watches that now dominate Red Square are the creation of the Butenop brothers from St. Petersburg. Installed between 1848 and 1851, these clocks are an engineering marvel. The complete mechanism weighs approximately 25 tonnes and includes a 9-metre pendulum weighing 32 kg. The musical chime is managed by a complex system of musical cylinders with pins, which activate hammers to strike the bells. The melody has changed throughout history, from the Internationale to the current Russian Federation Anthem. Their precision is legendary, maintained through meticulous care, ensuring that Moscow’s time is always exact.

In-Depth: Russian Watches in the Modern Era (Pages 55-64)

This section of the book, “Наши дни” (Our Days), traces the evolution of Russian watchmaking from an artisanal craft to a mass industry, a true symbol of Soviet progress.

- From Imports to National Production: Before the Revolution, Russia relied almost entirely on imported timepieces. The establishment of a national watchmaking industry became a strategic priority for the new Soviet state, not only to meet civilian demand but also for industrial, military, and scientific needs.

- Acquisition of Know-how: To accelerate the process, the USSR adopted a forward-thinking strategy: it acquired advanced watchmaking factories and technologies from leading countries in the sector, such as the United States and Switzerland. This allowed them to rapidly overcome the technological gap.

- The Birth of the First Moscow Watch Factory (1 МЧЗ): 1930 marked a milestone with the founding of the First Moscow Watch Factory. This factory became the engine of Soviet watch production, starting with pocket and wristwatches, then expanding its range to include table and wall clocks. Here, legendary brands like “Poljot” (meaning “flight,” a tribute to Soviet space achievements and, notably, the watches worn by Yuri Gagarin on the first space flight) and “Slava” (meaning “glory”) were born, becoming synonymous with robustness, reliability, and accessible precision.

- Mass Production and Accessibility: The Soviet watchmaking industry was geared towards mass production, with the aim of making timepieces accessible to every citizen. This contributed to a greater organisation of time in daily and working life. Russian watches gained a reputation for their durability and precision, earning popularity both domestically and internationally.

- Other Notable Factories and Specialisations:

- The Second Moscow Watch Factory (2 МЧЗ): Another key player in the sector, also producing the “Slava” brand, it distinguished itself with a wide range of models, including automatic watches and those with complications.

- The Petrodvorets Watch Factory: Located near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), it is famous for the “Raketa” (meaning “rocket”) brand. These watches were particularly valued for their robustness and precision, finding use also in military and professional fields.

- Beyond Civilian Consumption: The Russian watches industry was not limited to civilian timepieces alone. It was also crucial for the production of precision instruments for aviation, the navy, and the armed forces, including chronographs and on-board instruments, highlighting the high quality and reliability achieved.

- The Legacy of Precision: The final section celebrates the success of the Soviet watchmaking industry. In just a few decades, Russia transformed an almost non-existent sector into a powerful productive force, supplying millions of reliable and precise watches. This helped reinforce the idea that time precision is a fundamental element for progress and the organisation of modern society. Russian watches are, ultimately, a tangible symbol of a nation’s engineering skill and productive capacity.

This fascinating journey through time, guided by B. Radchenko’s book, reveals how Russian watches are much more than mere indicators of hours and minutes: they are custodians of history, culture, and technological innovation, reflecting the transformations of an entire country.